A day late for Valentine’s Day, but nonetheless, in honor of both Valentine’s Day and Black History Month, I’m doing something a little different and giving you a post not about a particular story (though I cover some of those as well) so much as a post about a particular author. I’ve been thinking of adding an “author spotlight” feature to the blog for a while now (highlighting various forgotten pulp romance authors, natch), and this seems like the perfect way to kick it off. So yes, today I’m talking about Gertrude Schalk (better known as Toki Schalk Johnson), an African-American author who wrote prolifically for both newspapers and the pulps. While there were likely other women of color (potentially even men of color) writing for the romance pulps back in the day, Schalk is one of the only ones currently known to us. I can only hope to uncover more in the future, but this is what I’ve got for now, so let’s dive in:

Gertrude Ruth Schalk was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Theodore and Mary Schalk. Records vary as to whether Theodore’s full name was “Theodore Girard Schalk” or “Theodore Otto von Schalk,” but there’s more evidence to support it being the latter, not least of which is that Gertrude (and even her sister) are occasionally recorded in newspapers with the last name “von Schalk.” (“Theodore Girard” was the name of one of their children (see below), so I suspect any record discrepancies are due to conflating father with son, or else misreading his middle initial “O” as a “G,” etc.) Mary’s middle initial was “A,” and her maiden name has variously been recorded as “Wilkinson,” “Wilkerson,” and “Dickerson.” Theodore worked as both a waiter and a musician in the early 1900s, and Mary also worked as a waitress according to the 1910 and 1920 censuses. Perhaps notable, the 1920 census lists their race as “Black,” but the 1910 census specifies them as “Mulatto.”

Accounts vary as to when exactly Gertrude was born. Her wikipedia page states she was born “Lillian” in 1906, but this is incorrect—Lillian was her sister (and was indeed born in 1906 according to Boston birth records—on April 28th of that year, specifically). The confusion perhaps comes from the fact that—much like Gertrude primarily went by the nickname “Toki”—Lillian would eventually go primarily by the nickname “Bali” (confirmed in the Boston Guardian newspaper from April 7th, 1951, which refers to her as “Lillian (Bali) Schalk”). Looking into census records and other ancestry data from the time, it seems reasonable to assume that Gertrude was actually born Hattie (potentially short for “Harriet”) Senobia (in one record spelled “Zenobia”), on June 11th, 1904. For reasons unknown (though I speculate on a possibility below), she appears to have changed her name sometime in the late-1920s—“Gertrude” is nowhere to be seen in records before then, but she suddenly pops up on the 1930 census, living with Lillian in an aunt’s house. Both women are listed as nieces to the head of the household, Nora E. Harris, and there is also a telltale two-year age gap between Gertrude and Lillian, as there would have been between Hattie and Lillian (though their stated ages, 24 and 22, would put them as being born in 1906 and 1908 instead of 1904 and 1906, respectively but anyone who’s ever done genealogy research knows that census records from back then can be WILD, and you could also lie about your age willy-nilly). Furthermore, Hattie Senobia—who was previously listed on censuses and whatnot—seems to disappear from the public record after the 1920s.

So, assuming that Gertrude and Hattie were indeed the same person, she would have been the oldest of her siblings. Lillian (middle initial “R”) would come next, followed by two brothers, George Otto (born June 28th, 1907) and Theodore Girard (born December 16th, 1912). Another sister, name unknown, was born February 18th, 1918, though it’s possible/likely that she died shortly after birth. (A fifth child is nowhere to be seen on the 1920 census, and it might be that the reason her birth record is missing a first name is because she was never actually given a first name.)

“Senobia” is listed as a waitress on the 1920 census, and on March 8th, 1924, at the age of 19, she married Herbert Campbell Freeman (born March 16th, 1897). The license lists her name as “Senobia H. Schalk” and her occupation at the time as “elevator operator.” Herbert’s occupation at the time was “chauffeur.” The couple appear to have had one child, a son George, who died shortly after birth (on August 13th, 1924) due to a cerebral hemorrhage. Herbert, himself, passed away four years later, on April 11th, 1928, from unknown causes. It’s possible that Hattie Senobia (or Senobia Hattie?—I’m still not sure about the name order) decided to change her name to “Gertrude Ruth” after this in an attempt to start over and move on. However, this is all speculation on my part.

Despite not living in New York, Schalk is often still associated with the Harlem Renaissance by virtue of her literary output. She was a founding member of the Saturday Evening Quill Club (also known as the Boston Quill Club), an African-American literary organization that published The Saturday Evening Quill (1928-1930), a short-lived but notable magazine that featured work by Eugene Gordon, Helene Johnson, Dorothy West, Florida Ruffin Ridley, and Edith Mae Gordon (just to name a very select few). Schalk, herself, published at least three stories in various issues, and one of them, “The Black Madness” (June 1928), made Edward J. O’Brien’s list of best short stories for that year. Another, “The Red Cape” (April 1929), can actually be found on the Internet Archive, as that whole issue has been digitized. While “The Red Cape” is not a romance by today’s standards (it doesn’t end happily), I still think it’s interesting in that it’s a story that revolves around the romantic relationship between two Black characters. (To summarize, sailor Pete returns home from a six-month stint at sea, and is looking forward to reuniting with his wife, Mamie, but when he sees her leaving what is implied to be the local brothel, he assumes she’s been stepping out on him. The truth, however, is far more tragic. Trigger warning for (highlight for spoiler) referenced infant death.) Yet another Quill story of hers, “Flower of the South” (June 1930), was collected in the 1996 anthology, Harlem’s Glory: Black Women Writing, 1900-1950, and can be borrowed from the Internet Archive if you can’t find it elsewhere. (“Flower of the South” is far more politically biting than “The Red Cape,” and follows white upper-class Englishman Hugh, who’s been visiting a Southern American senator and is overall very charmed by the experience—but his opinion swiftly changes when a racist lynching breaks out, and he finds himself particularly disgusted by the senator’s daughter, Betty, whom he’d previously been ready to propose to. Earlier in the story, Hugh learns about the concept of passing from a local “mammy,” which perhaps suggests Betty ironically has some Black ancestry of her own that she’s unaware of.)

In 1930, Schalk began writing for the pulps, selling her first story to Love Story Magazine (“Moon Magic,” which was published in the June 21st issue). She would go on to become a popular and prolific pulp writer, publishing primarily (according to The FictionMags Index) in Love Story Magazine and All-Story Love, though she dabbled in others. While pretty much all of her pulp output qualifies as romance, she did write what appears to be a handful of crime stories for The Shadow Magazine in the ’30s, usually under the name “G.R. Schalk.” A memorial piece written by Hazel Garland in the Pittsburgh Courier (May 7th, 1977) also states that she wrote for the confession magazines, but barring a discovery of her manuscripts somewhere, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know which of those were hers, as confession stories were almost always published anonymously. According to Brooks E. Hefner’s 2021 book, Black Pulp: Genre Fiction In the Shadow of Jim Crow, Schalk also published pulp work under the pseudonym “Gerry Ann Hale.” (Note: I have no reason to doubt this piece of information, but I also currently only have access to the Google sample of the book, which means I can’t check his source(s).) As Hefner notes, her pulp work was lucrative, providing her with a comfortable income that even allowed her to travel recreationally when a lot of the country was struggling.

During this time, at least as early as 1932, she was also involved in journalism, writing a society column for the Pittsburgh Courier (initially called “Smart Talk On Society In Boston,” later “Toki Types”). In the spring of 1943, she became Womens’ Editor of the paper, and moved from Boston to Pittsburgh to work in their main offices. On May 30th, 1946, Schalk married John Wesley Johnson III (born January 16th, 1903), a businessman and journalist who worked in Columbus, Ohio and who hailed from a prominent Detroit, Michigan family. The license states it was John’s first marriage, but this is incorrect—earlier records indicate he married an Elvira Harper in Ohio on November 15th, 1932. (Elvira herself was a widow at the time, whose maiden name appears to have been “Bell”; presumably she either died or she and John divorced, though I can find no documentation that points to one over the other.) Just for reference, John and Gertrude’s marriage license lists their ages as 42 and 40, respectively. There was nothing I could find to suggest the couple had any children.

Schalk’s fictional output slowed down in the 1940s, and—coinciding with the impending death of the pulp magazines—effectively ceased in the mid-’40s; her last known pulp story was published in the October 1946 issue of Gay Love Stories, though at least one more short story was published in the 1948 romance issue (No. 112) of the paperback series Pocket Reader Series. Schalk appears to have turned her writing efforts solely to journalism after this, becoming an important and influential figure in both the press scene and the Black community: In 1961 she became one of the first Black members of the Women’s Press Club of Pittsburgh, and was even elected president of the organization in 1970. Her sister Lillian also appears to have been involved in journalism, writing columns of her own, and—by the sound of it—even taking over Gertrude’s role in the Boston scene when Gertrude moved to Pittsburgh. Schalk continued her “Toki Types” column all the way until 1974.

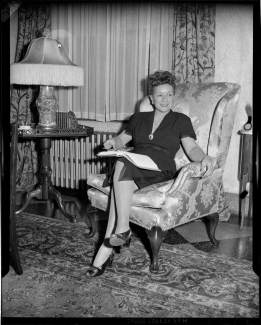

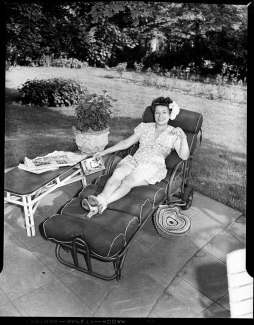

Her husband John seems to have died sometime in 1969. Schalk, herself, eventually retired to the Law-Den Nursing Home in Detroit with her sister (now firmly going by the name “Bali”), and passed away peacefully on April 23rd, 1977. According to the aforementioned memorial piece, there were no public funeral services, and she donated her body to science. A great number of pictures of her (and even some of her sister) exist as part of the Charles “Teenie” Harris collection at the Carnegie Museum of Art, and can be viewed online. By all accounts and appearances, she was a fashionable, vivacious woman:

Some select photos of Schalk from the early 1940s, August 1945, and the 1950s, respectively.

As far as Schalk’s romance output goes, I’ll be honest—it doesn’t typically do a whole lot for me. (Major caveat: All the stories available to me at the moment come from very early in her pulp career, so it’s entirely possible that she got better with practice. Hopefully I’ll be able to track down some of her later work, so as to increase my sample size, but at the moment, her early work is all I’ve got, so her early work is what’s being judged here.) Her heroines tend to be plucky working gals, which I dig, and more than once they physically save the hero’s life, which I dig even more, but the plots (so far) haven’t really interested me, and the stories themselves can suffer from weak structure. Nevertheless, knowing she was a Black woman writing for white supremacist publications lends an extra dimension to her work, and has succeeded in putting her firmly on my radar. (FYI, all of her romance stories currently available online or through my own collection, including the ones I specifically mention below, have been added to my Pulp Romance Guide with summary blurbs and story links. All are under the 1931 section, or else you can do a control-F search for her name, in the event you’d like to check them out for yourself.)

For starters, while all of her heroines can be assumed to be white (and indeed, their “white cheeks” or “white hands” are often referenced directly), I’ve noticed that almost all of them have dark hair. (I think, to date, only one has been anywhere near blonde?) Furthermore, while their skin color often is stated to be white or otherwise pale, there’s also often something unusual (though always left curiously vague) about their features. “A Girl Called Martha” (Love Story Magazine, December 19th, 1931) actually gets a little more specific, as we’re told the titular heroine’s “nose wasn’t exactly classical” and “her lips weren’t exactly shaped like a Cupid’s bow.” She also, notably, has brown hair and brown eyes. As such, I wouldn’t go so far as to say Martha is outright implied to be Black, the way the protagonist of Cornell Woolrich’s “One Night In Barcelona” is (different genre, white author, still a good story), but she could most certainly be read as something other than strictly white. As the photos above show, Schalk herself was a light-skinned Black woman, so this very well may have been an attempt on her part to write heroines who did indeed look like her, even if she couldn’t come right out and describe them as “colored.”

Of potentially greater note is “The Unknown Voice” (Love Story Magazine, April 25th, 1931), in that it has some interesting anti-colonialist vibes: Heroine Betty is a night-shift telephone operator, who gets a call from hero Howard, requesting a taxi to take him home from the train station. Betty sadly has to let him down, but happens upon him on her own way home in the early morning, and ends up saving him from an assassin (who runs off after his plan is thwarted). Howard, we find out, has just returned from India—he went there at the behest of his fiancée, who tasked him with retrieving a jeweled box from a temple to prove his love for her. Howard did so, but he also, yanno, pissed off the locals with his robbery, hence why one of them followed him back to the U.S. and is now trying to murder him. To Howard’s credit, he realizes he’s fucked up and needs to set things right:

Betty shivered. “Do you know who did it?” she whispered.

The man nodded shortly and his hand went instinctively to his coat to touch a small bundle that bulged his breast pocket.

“I know. I should have expected it,” he went on. “I might have known I couldn’t get away with it.” He looked at her suddenly and his eyes were touched with a faint fear. “You saved my life.”

“Oh, it was terrible!” Betty felt the old pain returning to her throat. Now that the excitement was over, her weariness was coming back.

“It was a man from whom I stole something,” Howard spoke grimly. “Something that I had gone almost around the world to get—for some one else.” For a moment he brooded silently. “I know I shouldn’t have done it. But that doesn’t help matters any now. I must return it, that’s all.”

Unfortunately (going back to those structural issues I mentioned), this is not the main focus of the story; instead, Betty almost immediately falls ill, and the whole thing morphs into a tale of hurt/comfort as Howard insists on caring for her at his fancy estate. The jeweled box subplot does get resolved with Howard returning it, but it happens off-screen, and you only hear about it at the very end, effectively as an afterthought. Still, it’s a refreshing change of pace when you compare it to all the other pulp stories of the era that gleefully and uncritically feature white characters adventuring in “exotic” locales.

Regarding Schalk’s potential work under the name “Gerry Ann Hale,” well, I have two Hale stories at my fingertips—“One Kiss” (Love Story Magazine, May 7th, 1932) and “Two In a Fog” (Love Story Magazine, March 30th, 1935). They both feature dark-haired heroines, sweet heroes, straight-forward titles, and relatively simple plots—all things consistent with the “Schalk” stories I’ve read, which would support the idea that they were in fact written by the same person. Other similarities include character names (“Martha,” “Hugh,” etc.), and “Two In a Fog” even features a catty, antagonistic “other woman”—a character type/trope I’m not personally fond of, but is nevertheless recognizable from some of the stories published under Schalk’s own name. Neither of the two Hale stories are as socio-politically interesting as “The Unknown Voice” (or even “A Girl Called Martha”), but still, I’ll have to be on the lookout for more of them. (As before, if you’re interested, you can find both Hale stories through the previously-linked Pulp Romance Guide. I found “Two In a Fog” disappointing overall, but “One Kiss” is solid and surprisingly sexy for the era—even though the censorship practices of the day mean the hero rather hilariously has to pull up a chair when he’s about to kiss the heroine, as opposed to just joining her on the bed, pfft.)

Anyway, that’s it for now—thanks for reading, and I hope you’ve enjoyed this post! If you’re looking for further related information, might I recommend:

- Brooks E. Hefner’s previously mentioned book Black Pulp. While not specifically about romance, it does have a whole section on Black love stories, and appears to mention Schalk more than a couple times.

- Queen of the Pulps by Laurie Powers. While first and foremost a biography of Love Story’s editor, Daisy Bacon, I think it also serves as a good intro/overview of the romance pulps, themselves. Powers discusses Schalk at some points, and the book even includes a reprint of part of an astrological spread (originally featured in a 1935 issue of Ainslee’s Smart Love Stories) that has a picture of her.

- Much like Schalk wrote white romances for the pulps in the 1930s and ’40s, romance historian Steve Ammidown recently wrote a post about other Black authors who (initially, at least) wrote white romances for category lines in the 1980s.

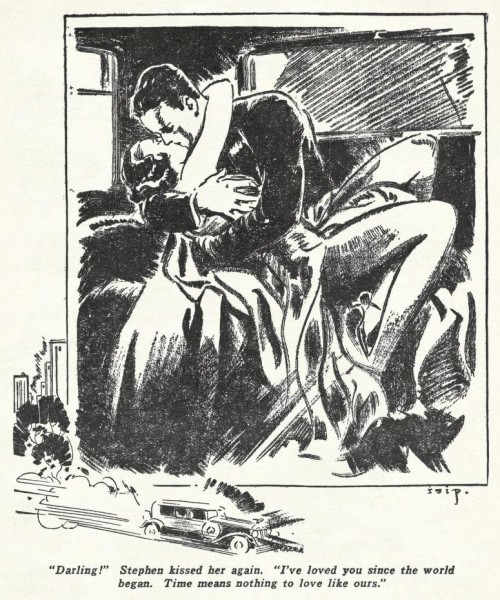

And now, since I like to end my posts with a picture if I can, I’ll leave you with this illustration from Schalk’s “Gerry of the Chorus” (Love Story Magazine, October 3rd, 1931). It’s one of her stronger outings (again, from what’s currently available), and features this bangin’ clinch by Pagsilang Rey Isip, a Filipino artist. <3

Tagged: 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, all-story love, Author Spotlight, gerry ann hale, gertrude schalk, love pulps, love story magazine, pulp, romance, short stories, toki schalk johnson

Leave a comment